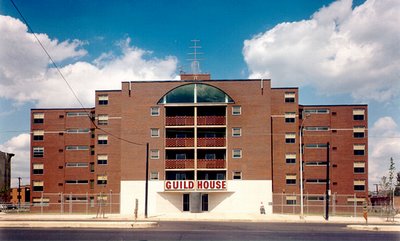

[all photos: Venturi Scott-Brown Associates]

[all photos: Venturi Scott-Brown Associates]

I had a chance to swing by Columbia last night for a presentation by Bob Venturi, followed by a discussion between the architect and GSAPP dean Mark Wigley. You are probably rolling your eyes, since I seem to always have Venturi and his wife/partner Denise Scott-Brown on my mind. But indulge me once again -- there were some interesting moments worth sharing.

The event was loosely structured as a celebration of the 40-year anniversary of the publication of Venturi's seminal debut book, Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture (1966). For those who haven't read this -- you should. It is absolutely one of the most essential texts (along with Venturi's 1972 follow-up, Learning from Las Vegas, co-authored with Denise Scott-Brown and Steven Izenour) for understanding the predicaments facing contemporary architecture. After a stirring introduction by Lee Bollinger, Columbia's president and Venturi's old client back at Michigan, Venturi began with some brief reflections on both the book's inception and critical reception. Reiterating comments he has made over the years in various articles and symposia, he insisted that interpretations of the book or of him as being anti-modern or postmodern are completely misguided. This has always been pretty clear to me -- the book, while celebrating the immense stylistic diversity of historical architecture, by no means prescribes a specific style. Rather, it advocates an approach of celebratory, almost hedonistic, eclecticism -- or what Venturi likes to refer to as mannerism. While much of VSB's architectural production has involved neoclassical elements or historical references, the style itself is arbitrary and almost besides the point. [And furthermore, in line with Venturi's claim last night that Complexity and Contradiction ultimately affirmed a functionalist approach to architecture, almost all of the VSB work follows a strict functionalist paradigm of boxy, ultra-efficient floorplans that often divorce service spaces from served spaces. A reference to Kahn, no doubt, to whom Venturi also paid tribute tonight. The functionalist imperative appears again and plays a huge role in Learning from Las Vegas.] Anyway, the point is that it's understandable why historicist postmodern architects latched on to Complexity and Contradiction as justification for their stylistic carelessness, but the sweet irony is that, in true form, they completely missed the intricacy of Venturi's argument.

The discussion consisted mostly of Wigley's characteristic wizardry with words that seemed to completely baffle poor old Bob. He essentially asked the same question -- why did you write Complexity and Contradiction? -- a dozen times in a dozen different ways. The hope was to elicit some sort of polemical commitment to manifesto-writing and the activist potential of theorizing (to which I fully subscribe), but Venturi simply refused to cede Wigley any ground, insisting that the book grew out of his lectures for a theory class he was teaching at Princeton in the early 60's. I wondered if Wigley was actually talking less about Venturi and more about himself: if he was trying to posit a projective role for the writer in order to justify his own career as a non-practicing architect. Maybe that's getting a little too Wigley-psychoanalytic. Who knows. Anyway, the banter continued at length until Denise Scott-Brown, who, like the rest of us, could not take any more of the labyrinthine inquisition, finally decided to tell him what he wanted to hear. "Bob writes to figure out what he thinks," she said, explaining how the writing indeed came to inform their practice. Whether she was actually sincere, or whether she was just doing us all the favor of neutralizing the debate, I'll never know. But her brief words made me want more. Even though the event was nominally in honor of Complexity and Contradiction, which Venturi wrote solo, I realized (yet again) that Venturi without Scott-Brown is really only half the story.

The most interesting part of the evening was Venturi's emphatic characterization of his own writing as purely pragmatic and realist, as opposed to purely idealistic. In other words, he claims the basis of his learning and his analysis is always the existing conditions, the ordinary, the "real" world as it is, and that conclusions are never drawn from any preconceived ideologies. Hence the "Learning from..." technique that proved so crucial in the later collaboration with Scott-Brown and Izenour.

Clearly this enchantment with the messy realities, chaos, multiplicities, and vibrancies of everyday life is what really defines the Venturi Scott-Brown legacy. It certainly explains why I identify so strongly with their work. And seen in that light, it becomes evident why a school like Columbia would kick off its heavy-hitter lecture series with an event honoring good old Bob Venturi, who is still considered a postmodern pariah by many orthodox practitioners of architecture. It's definitely time, as architects as diverse as Koolhaas and FAT have come to realize, to reconsider the Venturis and their influence over the past forty years. Not only are they "back," as I've said - but maybe they never actually left.